As tango lovers we all know the habanera rhythm, don’t we - pamm padam pam, pamm padam pam:

We know that it was prevalent in guardia vieja tango before 1920, but after that it can only be found in milonga and European tango. How could it just vanish from guardia nueva tango in just a few years? Well, it didn’t, it was transformed into something else. But before tracing Habanera’s footprints into guardia nueva, let’s go back to where it came from.

The Origins

As the name suggests, habanera has got something to do with Havana and Cuba, but in Cuba this music and dance style was called contradanza, not habanera. As a dance, contradanza was derived from English country dance and came to Cuba through France and Spain. The music, however, was based on rhythms from another continent.

Atlantic slave trade meant a mass-scale deprivation of human rights, but it also turned the New World into a melting pot of cultures. Many traits of West African music found their way into Latin American music, and the most important of them was a rhythmic cell named tresillo.

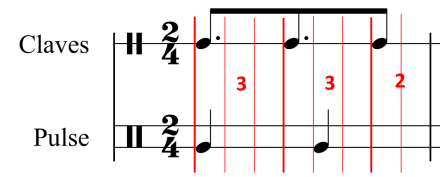

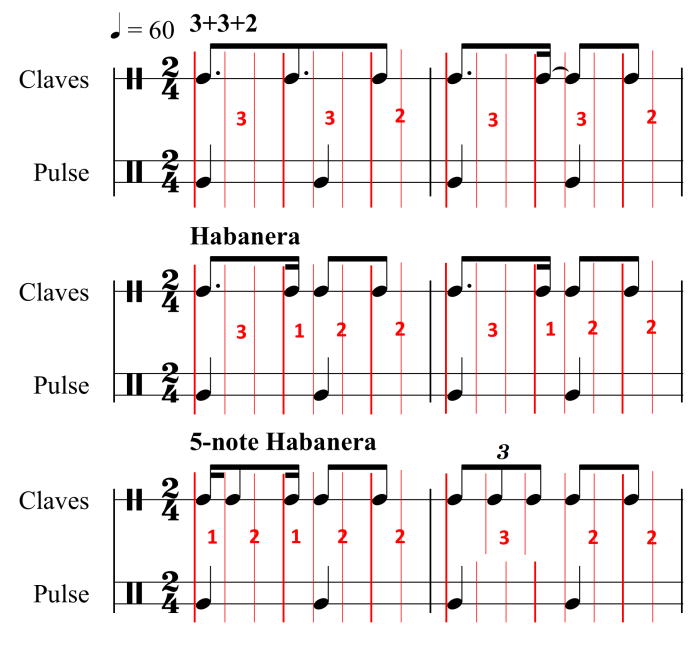

West-African music makes extensive use of polyrhythm, i.e., the layering of different rhythms on top of each other. The common tresillo pattern used habanera is a compound of two tresillos, 3 units of duration each, plus a note of two units, and this is layered on top of a beat of 4 units. Typically, this 3+3+2 pattern is played by the claves, and the 3+3+2 ticking can be heard in a number of styles of Latin music.

If we add a note to the claves part simultaneously with the second pulse beat, we will get the habanera rhythm, which equals to 3+1+2+2 = 8 = 4+4. In the following compilation of rhythms, we first have two bars of 3+3+2 in two alternative notations (which sound identical), then two bars of habanera and then two 5-note variants of habanera.

The 5-note variants are mainly used in melodies and less frequently in accompaniment. The latter one, with a triplet, adds another rhythmic level and reflects an alternative habanera rhythm of 2+2+2 against 3+3, but we won’t go any deeper into that because it would involve some higher-level arithmetic. Anyhow, in melody, the 5-note rhythm is often sung or played somewhere between these two variants, and this even manifests itself in tango phrasing.

This is how these rhythms sound when played. Please view the video as many times as you like!

Compilation of tresillo-based rhythms

Now let’s listen to a habanera published somewhere around 1860 by the Spanish composer Sebastián Iradier. He had toured Cuba a few years earlier and was so impressed by Cuban music that he wrote a series of habaneras, some of which are very well known and even found their way to opera and tango. The following one, named El chin chin chan is not as famous as La paloma or El arregelito (“borrowed” by Georges Bizet as Carmen’s Habanera), but it has a nice claves rhythm – sure you can hear it? Also play attention to the recurring 5-note pattern in melody!

El Chin Chin Chan

Tresillo Rhythms on the Pampas

Tresillo-based rhythms were so widespread and prevailing in Latin American music that it would have been a miracle if none of them were found on the Pampas of Argentina and Uruguay. It is possible that they came through Cuba and the countries between, but it is more likely that they were brought directly by black slaves, just the way what happened in Cuba. After all, at the beginning of the 19th century, about 30 % of the population of Argentina and Uruguay consisted of African slaves.

One of the endemic manifestations of the tresillo rhythm in Argentina was the bordoneo guitar accompaniment of milonga campera. It faithfully repeats the 3+3+2 pattern and was even more popular among the payadores of the Pampa than the common habanera rhythm. This video demonstrates a typical bordoneo passage.

Guitar bordoneo

I recently wrote another post about the significance of the bordoneo in tango music, and there I also explain the term marcato, which pops up in this post a few paragraphs below.

Habanera and Early Tango

Music in habanera rhythm was also commonly known as congo, tango-congo, or tango. All these words date back to West-African languages. Thus, it was quite natural that when something called tango emerged in the streets and humble cafés of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, it had a strong connection to habanera.

El entrerriano by Rosendo Mendizábal (1868 – 1913) is considered the first published tango. It was composed and published somewhere between 1897 and 1898 and bears a clear and consistent habanera rhythm in the left hand:

A decade or so later, Roberto Firpo (1884 – 1969) and Juan Maglio (“Pacho”, 1881 – 1934) were among the first to publish and record tango music, and here, while Pacho performs Firpo’s composition La gaucha Manuela, recorded in 1913, nobody can avoid hearing the habanera rhythm.

La Gaucha Manuela

But wait! Was there something familiar in the B section of this tango? Let’s go a bit further!

In 1916 Firpo was in Montevideo with his orchestra when a young student named Gerardo Matos Rodríguez wanted to show him a little march he had composed for a traditional carnival procession called comparsa or cumparsa. The march was titled La cumparsita. The maestro agreed to play it, but because the march only contained one section, Firpo added some material from La gaucha Manuela and another tango named Curda completa. Quite soon Firpo also recorded this joint creation but he never got credit as a co-author because Matos Rodríguez insisted on having the composition under his name only.

"La cumparsita" - Grabación original - Noviembre de 1916 - Roberto Firpo

The A section of La cumparsita is clearly a march with a uniform walking marcato in dos por cuatro with an arrastre marking the first beat in each measure. But when the B section starts at 0:51, we hear the habanera rhythm of La gaucha Manuela. It’s a bit obscured, but it’s there all right! This way La cumparsita stands one leg in the past and the other in what is to come.

The Decline and Rebirth of Habanera

Maybe La cumparsita made Firpo and other musicians realize that there can be tango without habanera. Consequently, Firpo’s interpretation of Nueve de julio from 1917 bears no trace of habanera rhythm – just marcato. Perhaps the simple marcato beat was preferred by immigrants from Europe who wanted to dance simple tango.

9 de Julio · Orquesta Típica Roberto Firpo

After just a few years musicians realized another thing: Basing the accompaniment solely on habanera or solely on marcato makes boring music, so some variety was absolutely needed. Help was to be found from the 5-note habanera pattern we listened to in El chin chin chan.

The 5-note habanera pattern had found its way to tango melodies from the very beginning and was frequent in them even when habanera had disappeared from the accompaniment. In Paramount (1923) Francisco Canaro emphasizes the 5-note melodic pattern with accompaniment and finds a new rhythmic phenomenon. The first occurrence is at 0:11.

" Paramount " (tango) orq. tipica Francisco Canaro . grab. (1923).

This rhythm, called sincopa, should be familiar to all tango lovers.

As a general musical term, sincopa (syncopation in English) means shifting the regular musical accent off-beat, typically by tying an accented note to the preceding one that now receives the accent. In tango, the tie is emphasized with a strong arrastre, which kind of drags the accent over the bar line. You can read more about arrastre in a previous post in this blog.

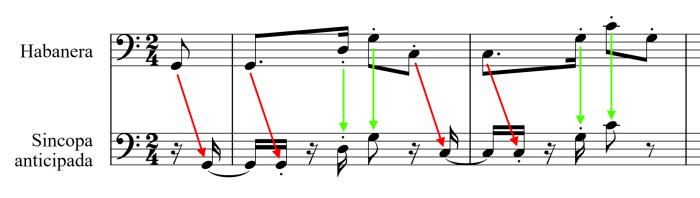

As I already hinted, sincopa is the direct descendant of the habanera pattern. Tango musicians speak of two kinds of sincopa: sincopa anticipada (the example above) and sincopa a tierra. Sincopa anticipada can be seen as a mutation of habanera where the first and the last note have been shifted a semiquaver (1/16 note) forwards whereas the two middle notes remain intact – follow the red and green arrows, respectively.

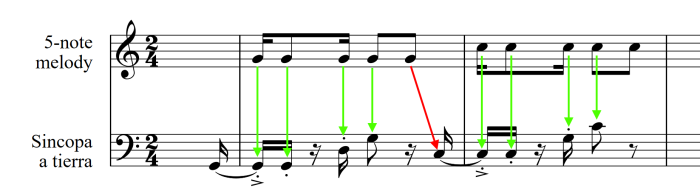

The other type, sincopa a tierra, is almost identical to the 5-note pattern, just the last note has been converted into an arrastre. Here a tierra (“towards the ground”) suggests that this version is heavier than sincopa anticipada, which is due to the fact that the first note in a bar is really played with an accent, not just “anticipated”. And, of course, the syncopated rhythm has quite a different character than a 5-note habanera pattern in melody.

Please note that in these examples, to make the comparison simpler, the sincopa is only written to the bass staff. In real orquesta típica texture, the sincopa is an interplay between the double bass and the bandoneon.

In 1929, when Canaro recorded his version of Don Juan, a guardia vieja tango from 1910, the habanera rhythm was practically extinct. In his arrangement Canaro left off the habanera bass that was consistent all over the original sheet music but kept the 5-note habanera rhythm in the right-hand part of the piano turning it into a powerful sincopa a tierra.

In the recording, sincopa a tierra dominates the whole A section from 0:04 on. The B section is accompanied by marcato, but when the A section returns at 1:11, we hear some rhythmic extravaganza based on syncopated 3+3+2 rhythm. The sincopa returns at the end after the variación. This arrangement was probably written by Luis Riccardi, Canaro’s pianist for decades.

Francisco Canaro - Don Juan

Habanera Ever Since

After the mid-1920s, the alteration of marcato and sincopa has been the primary rhythmic fuel of tango up to the present day. The habanera rhythm has survived in such styles as

- tangos in guardia vieja style played by retrospective quartets and quintets like Cuarteto Roberto Firpo and Canaro´s Quinteto Don Pancho and Quinteto Pirincho,

- in milonga ciudadana that mainly replaced the bordoneo accompaniment of milonga campera with habanera rhythm,

- to some extent in tango canción, mainly for a nostalgic effect, and

- in European tango, also to some extent.

Why habanera was preserved in European tango is another story, which I might write about another time.