At the last milonga we had before the pandemic, a DJ friend marveled at Láurenz’s valses and said there must be something special in them because they are so compelling to dance to. This interpretation of Paisaje by Piana and Manzi was her favorite:

Paisaje - Pedro Laurenz - Alberto Podestá 1943.08.06

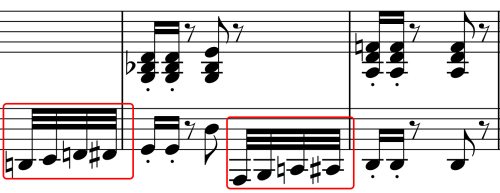

I couldn’t say anything specific then, but afterwards, when I listened Paisaje once again, it was pretty clear to me what made it so special: The pianist was playing arrastres with his left hand. A piano arrastre is a quick chromatic movement of 2 to 4 notes towards the downbeat.

Playing arrastres is commonplace in tango interpretations, but with valses they are rarely used. When playing a vals, most golden-age tango pianists play strong but relatively short bass notes, typically using the little finger of their left hand. In Paisaje, however, the pianist uses 4 to 5 fingers to play the bass note when an arrastre is involved and then keeps it sounding longer than other pianists. Just as in tango, the arrastre creates a strong sensation of forward movement and kind of lifts the dancers’ feet off the floor – that’s the effect my DJ friend must have referred to.

When investigating a bit further, I found out that it was only Pedro Láurenz and his orchestra who used this kind of distinctive arrastre in valses. From Flores de alma (1942) till Temblando (1944), the pianist applies it, more or less, to bass notes that need structural emphasis. But who was this pianist that developed a unique style of playing the bass line?

When Láurenz formed an orchestra of his own in 1934, his first pianist was Osvaldo Pugliese, but from 1936 on this post was held by Héctor Grané who also wrote the arrangements for the orchestra. There were pianists who had a substantial impact on the orchestra they were playing in, such as Biagi on D’Arienzo, Goñi on Troilo, or Maderna on Caló, but Grané is never mentioned in this party. This began bothering me: If Grané could develop a piano style that made Láurenz’s valses so unique, what else did he contribute to the orchestra, not only as a pianist but also as an arranger? Because no other arrangers are known from the period when Grané stayed with Láurenz, his role must have been significant.

But before we try to figure out Grané’s influence on Láurenz’s music, I would like to sum up something about the role of an arranger in tango music. If you are a seasoned musician, you might want to skip this chapter.

What Does an Arranger Do, Anyway?

Tango Is Arranged Music

The tango that emerged at Río de la Plata in the late 19th century and early 20th century was based on popular song. Early tango bands just played the melody with some rhythmic accompaniment and simple chords. If the group had instruments that could alternate in playing the melody or the accompaniment, the musicians might have negotiated who plays which part in each section of the piece. That was their arrangement.

When tango became popular among higher social groups, the audience wanted more exciting things to happen in the music. Also, to meet the growing demand, professional musicians had to play a huge amount of music at live performances and recording sessions without wasting time on negotiations. A written arrangement allowed them just to play their part and then move to another tango.

Tango was never improvised music the way jazz is. A group of experienced tango musicians might play a la parrilla, without a written arrangement, but in this case their shared stylistic knowledge guides the performance.

Where Did Arrangers Come from?

Naturally, an arranger must be able to read and write music, but that’s not all. They have to know how to use chords and combine melodic lines, i.e. know harmony and counterpoint. Traditionally, these subjects have been part of a pianist’s classical training, so it’s no wonder most arrangers have been pianists or at least have had the piano as their side instrument. In addition, mastering the piano keyboard helps visualize chords and melodies in one’s mind.

Bandoneon playing, on the other hand, was not taught at conservatories, and practically all bandoneonists who acted as arrangers had also had studies in piano and/or harmony and counterpoint.

But if the orchestra leader didn’t have the necessary skills to be an arranger, it didn’t mean that he had no role in the process of arranging music for his orchestra. The leader, who was responsible of the style and sound of the ensemble, always had the final word on every arrangement. For instance Aníbal Troilo, who could not write music himself, was notorious for rejecting some parts of almost all arrangements when he heard the result at a rehearsal. That’s why the score and part material found in Troilo’s cupboard is full of strikeouts and corrections.

The Song

An arrangement starts from a given song. The song might be a plain melody or come with an outline for accompaniment. It can be the arranger’s own composition or the creation of a fellow musician or the orchestra leader. If the composer cannot write music, he or she might sing, hum or play the melody to the arranger who jots it down on paper.

The typical way of getting a piece for an arrangement was to buy sheet music – one of those four-page leaflets with two pages of printed music containing a simple piano arrangement of a new song. The “arrangement” is not exactly the right word here because the piano texture was not meant to be performed. It just aimed to give an idea of the song with composer’s (or editor’s) suggestion for harmonies, rhythmic accompaniment, possible counter melodies, etc. So sheet music is just the starting point for the arranger.

Arrangers may keep the harmonies found in sheet music or change them on their choosing. The same goes with rhythm and even the form of the song: It is not uncommon that the arranger has changed the order of the A and B parts of the melody or written a new introduction. However, the most creative part in the art of arranging is adding new melodies. These melodies may support the original song melody as an accompaniment or have a melodic curve of their own and yet fit in the same harmonic context with the melody. “Rivaling” melodies of this kind are called counter melodies, and the art of writing them is called counterpoint.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Thinking

When musicians see an orchestral or choral score, they can read it horizontally or vertically. In the horizontal direction, there are melodic parts for each instrument or singer or a group of them. In the vertical direction, there are harmonies (i.e. chords) composed of notes played by each part. When a composer or an arranger writes a score, it is a matter of style how independent the voices will be or how tied they will become to each other.

Homophony vs. Polyphony

Since Renaissance, these two approaches to creating music have been called polyphony and homophony. Homophony is the vertical approach where one melody dominates the whole texture and other voices just accompany it, for the most part in the same rhythm.

Lassus | Matona, mia cara [á 4; The Mirandola Ensemble]

A special case of homophony is melody with chord accompaniment, for instance, a singer strumming chords on a guitar. The accompaniment might repeat a rhythmic pattern not found in the melody, but the individual notes in the chords don’t matter, just the harmonies.

In polyphony, the voices flow independently, and often melodic themes “chase” each other in different voices. This is called imitation.

Kyrie - Missa Papae Marcelli - Palestrina

Adding Some Color

Once we have written the voices, we will have to assign them to the instruments of our band. This is called instrumentation or orchestration. When we write for a large orchestra, several groups of instruments will be available in our palette, each with their own tone color or timbre: strings, four choirs of woodwind, three choirs of brass, and an assorted collection of percussion instruments (including piano).

In an orquesta típica we only have violins, bandoneons, and piano, but each of them comes with a set of registers of different color. For instance, a melody played on the lowest range of the violin is quite different in color and character when played two octaves higher. Violins and the double bass can also be played pizzicato (plucked) instead of arco (with the bow). There are also many special effects like the cricket-like chicharra or the drum-like golpe en la caja, i.e. slapping the back of the double bass with one or two hands.

And the bandoneon is in fact a combination of two distinctive instruments, the bright right-hand end and the velvety left-hand end. When a highly expressive bandoneon solo is needed, the arranger writes it for the left hand.

Arrangement to Performance

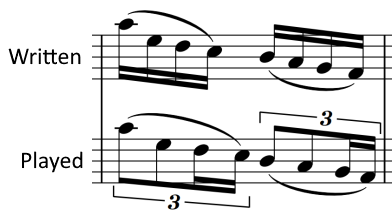

Now we might think that our arrangement is complete, but a tango arrangement is only finished when performed. As a rule of thumb, tango is written in simpler note values than performed, and what happens at performance is called fraseo, phrasing. When tango musicians play a passage, they start it slightly slower than written, then accelerate, and end up in shorter note values than written. This would be a typical phrasing of a four-note legato passage:

About Pedro Láurenz and His Orchestra

Musical Background

Láurenz started his music studies with the violin but switched to bandoneon at the age of 15. As a professional musician, he debuted in lesser-known orchestras, but decisive for his career was then his membership in the sextet of Julio De Caro.

In 1925 Láurenz became the second bandoneonist in De Caro’s sextet alongside the legendary Pedro Maffia, Láurenz’s idol long before joining the sextet. When Maffia left the sextet in 1926, Láurenz became the first bandoneonist until 1934. In this photo, he plays the first bandoneon on the right and Armando Blasco “El cieguito” the second.

Sexteto Julio De Caro has been considered revolutionary in the context of their time when tango was square and straightforward. Elastic treatment of melody and rhythm combined with rich harmonies are their trademarks. Julio De Caro’s elaborate violin playing, full of portamenti and small embellishments, often dominates their performances. Even the bandoneons mimic his violin portamenti by filling melodic intervals with quick chromatic passages between the notes. De Caro’s way of making music is like modeling wax in one’s hands while others, like Francisco Canaro, build their music from blocks of wood. Unfortunately, tango dancers have always preferred clearly structured music, even if it is made of blocks of wood.

Perhaps the most emblematic recording in their work is Flores negras, a tango by Francisco De Caro, pianist of the band and Julio’s elder brother. Here Julio De Caro plays the Stroh violin (depicted above), an instrument favored by jazz violinists during the era of mechanical recording technique. The recording is from 1927.

Julio de Caro - Flores negras

Neglected by dancers, De Caro did have a significant impact on other musicians. The followers of his ideas have been called the Decarean School, La escuela decareana, its most prominent members being Osvaldo Pugliese and Pedro Láurenz. Beyond this school, Decarean ideas can also be seen as a precursor of the highly melodic tango that emerged in the 1940s.

During his stay with De Caro, Láurenz composed 13 tangos, some of them with Julio De Caro or Pedro Maffia. All of them were recorded by the sextet.

Orquesta Típica Pedro Laurenz 1934 -1936

With his own orchestra, Pedro Láurenz first appeared at Café Los 36 Billares and the following year also on Radio Excelsior. As said before, the pianist at that time was Osvaldo Pugliese.

We don’t know if Pugliese was already exposed to De Caro’s music but joining Láurenz’s orchestra surely opened his eyes to Decarean ideas. During his early recording career from 1943 to 1945, he repeatedly paid tribute to Julio and Francisco De Caro – just like Láurenz did a few years earlier.

In 1936 Pugliese quit with Láurenz and was replaced by Héctor Grané.

Who was Héctor Grané?

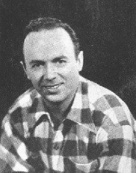

Information is sparse about the life of Héctor Grané. He was born on May 23, 1914 in Maipú, province of Buenos Aires. Internet sources don’t reveal anything about his family or musical education, and even his date of death is unknown. Were he still alive, he would be 107 years old – not very likely!

Pictures of him are also scarce, but this one, printed on many record sleeves, is from the late 50s.

So practically all we know about Héctor Grané is through his music. More than thirty compositions are attributed to him, almost all of them tangos. We can listen to his arrangements and piano playing on more than one hundred recordings, 62 of them made in Argentina and more than 40 made in Europe. To me, this seems a fair amount of legacy to assess him as a musician.

Years with Láurenz

The Decarean Period

In 1937 Láurenz finally got a recording contract with Victor. The first two pieces he recorded were of his own composition, namely Milonga de mis amores and a ranchera named Enamorado. The first tango he recorded, two months later, was Abandono composed by Pedro Maffia to lyrics Homero Manzi. This choice, a tango Láurenz had already recorded with De Caro in 1928, was symptomatic of what was to come. Let’s listen to De Caro’s version first!

Abandono - Sexteto Julio de Caro

Láurenz’s version differs from this in structure because there is a sung estribillo and a variación at the end. At first hearing, the first halves of the recordings don’t seem very different, but the more you listen to them, the more differences you will find.

ABANDONO-PEDRO LAURENZ-HECTOR FARELL

What hits the ear from the very beginning is that the mood is different. De Caro’s elastic violin playing is gone, and although the first violin leads the melody, it is not soloistic like De Caro’s. The articulation is resolute, at times quite aggressive, e.g. at 0:15. Unlike with De Caro, bandoneons double the violin parts, either an octave below or in unison. This makes an effective orchestral tutti and results in a very homophonic texture. Grané’s piano comments and bridges are also much more determined than Francisco De Caro’s. While the tempo is also faster, the overall feeling is that De Caro’s lingering melancholy has been replaced by anxiousness, and elasticity has given way to rhythm.

Of course, there are many similarities between these two interpretations, especially in the bandoneon section. Although the arrangements are not identical, the bandoneon soli at 0:35 and 0:33 don’t sound very different, which is no wonder because the first bandoneonist is the same person in both bands.

We might ask why Láurenz’s first choice for a tango was one he recorded with another band almost a decade earlier. Perhaps he said to himself: “This is how it should have been played back then” or “This is how it should be played today” – we don’t know, but it almost seems like Láurenz had a bone to pick with De Caro, and this determined his stylistic choices for the next five years.

At first, Láurenz’s visits to Victor’s recording studio were quite infrequent. In 1938 he made just one shellac with his own composition Vieja amiga on the A side. It was a tango to lyrics by José María Contursi. The singer here is Juan Carlos Casas with whom Laúrenz made ten recordings from 1938 to 1940 and five more in 1942.

PEDRO LAURENZ - JUAN CARLOS CASAS - VIEJA AMIGA - TANGO - 1938

Melody leads the homophonic texture, and it is not hard to imagine how this tango would have sounded like if played by Julio De Caro. However, Grané’s rhythmic piano texture is something Francisco De Caro would not have played, and it ties the melodic phrases together into an enjoyable and danceable continuum. Violin pizzicatos behind the singer and the bandoneon solo are a refreshing idea. Vieja Amiga seems to have been a minor hit because both Aníbal Troilo and Francisco Canaro recorded it a few months later.

Láurenz’s greatest hit from this period is undoubtedly Amurado composed by Láurenz and Maffia to lyrics by José De Grandis. It is also from the repertoire of Julio De Caro, and what I said earlier about Abandono also applies here. The difference, though, is even more pronounced, and here Láurenz plays with full self confidence showing that this is how tango should be played – including the dazzling variaciónes. There is little room for the arranger, but Grané plays with strong articulation that matches Láurenz’s idea of the piece.

Julio De Caro - Amurado

Today's Tango Is... Amurado - Pedro Laurenz 29-07-1940

The last tango from De Caro’s music album was Orgullo criollo that Láurenz recorded in September 1941. After that, things were to change.

Towards Accented Melodic Style

In 1941 Láurenz must have realized that he could not remain stuck to De Caro for the rest of his career. Golden Age of tango was near its culmination, and all successful bands were playing in a style I have called the accented melodic style. It involved using piano arrastres, the sincopa and marcato en cuatro accompaniment on the rhythmic side, and more horizontal thinking on the melodic side, including independent counter melodies. If Láurenz felt this was something he couldn’t master, the most effective way to enter the new style would have been to give more leash to Grané, and I think that’s just what he did.

The first attempt towards this direction was Quedate tranquilo, recorded in December 1941, but with Al verla pasar, recorded in January 1942 with Martin Podestá, the new style has really arrived. The tango was composed by Joaquín Mora, and the lyrics were by José Maria Contursi.

Al verla pasar - Laurenz

Now we can hear all the style features mentioned above. Just listen how Grané keeps a danceable pulse with his marcato and how arrastres and sincopas emphasize musical key points. The violin obbligatos behind the singer are most delicate, and there is also a piano solo à la Rodolfo Biagi (and others). All this said, the outcome yet sounds like Láurenz, especially the bandoneon soli at 0:30. And, of course, Láurenz gets his variación at the end.

In 1942 Láurenz recorded six more tangos in the new style, more or less, but none of them became a big hit. It is the valses, however, that we frequently hear at present-day milongas. Láurenz ended his recording year with María Remedios, a vals by Germán Teisseire and Carlos Pesce. The singer is Alberto Fuentes, and this is the one and only recording known from him.

Pedro Laurenz Y Alberto Fuentes Maria Remedios VALS 1942

A Second-rate Orchestra?

During the first six years of his recording career, Láurenz recorded seventeen tangos, eight of which were composed by himself or Pedro Maffia. What was missing were big hits of the day like Cuartito azul, Tormenta, A quién le puede importar, Quiero verte una vez más, En esta tarde gris, Al compás del corazón, Mañana zarpa un barco, Tristezas de la calle Corrientes, and Moneda de cobre. At Victor they were assigned to best-selling orchestras like Fresedo, Di Sarli, Troilo, Tanturi or Lomuto.

If Láurenz were offered a new hit piece, would he have rejected it? Probably not. He already had an arranger capable of adapting his orchestra to mainstream style, but he couldn’t find a singer that would appeal to the masses.

Enter Alberto Podestá

In 1943 Láurenz won in the lottery. Alberto Podestá, a rising star, had been singing with Carlos Di Sarli for a year but was totally fed up with his bullying colleague Roberto Rufino and Di Sarli’s poor staff management skills. After a couple of months of thinking about what to do, he decided to join Láurenz.

At their first recording session on April 16, two classics were cut on shellac: Nunca tuvo novio, an old tango by Agustín Bardi, and Veinticuatro de agosto, a new composition by Láurenz.

NUNCA TUVO NOVIO - LAURENZ PODESTA

24 DE AGOSTO - LAURENZ ALBERTO PODESTA

When listening to these masterpieces, don’t let Podestá’s charisma dazzle you from hearing the excellent work Grané has done with the arrangements. They are full of ever-changing details that make a living musical texture, and Grané at his piano keeps everything together. This richness, however, is always musically justified and works for danceability, not against it. The details don’t disturb a less-experienced dancer but provide the advanced with a lot of things to express in their dance. This is accented melodic tango at its best!

Soon after these recordings, Láurenz switched the record company from Victor to Odeón. I’m quite sure he didn’t have to knock on doors. On the contrary, when the management at Odeón heard Láurenz with Podestá, they must have made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

A First-rate Orchestra 1943 -1944

With Podestá and Grané, Láurenz was now at the leading edge of Golden-Age tango. Rivaling orchestra leaders in the Victor camp monitored carefully what Láurenz did and often, “inspired” by him, recorded the same pieces a few weeks or months later.

Láurenz and Podestá recorded Que nunca me falte and Recién in September 1943, and Ricardo Tanturi and Enrique Campos followed them in November and March, respectively. Recién is a tango by Osvaldo Pugliese and Homero Manzi from the same year. Interestingly, Pugliese himself didn’t record it until 1980.

RECIEN-PEDRO LAURENZ-ALBERTO PODESTA

RECIEN - TANTURI CAMPOS

Tanturi’s version is simpler but not bad at all. One difference I would like to point out is how Tanturi uses his bandoneons for sharp marcato accompaniment, especially during the vocal part. Láurenz and Grané never use the bandoneon section this way. Instead, they give the task of playing marcato to the violins. The reason behind this must be that to them the bandoneon was a melodic instrument, not something like the orchestral guitar that strums chords and rhythm.

With Di Sarli and Rufino there was a kind of tennis match going on from October to December 1943. The first serve was by Di Sarli and Rufino who recorded Yo soy de San Telmo, a milonga by Arturo Gallucci and Victorino Velázquez, on October 7. Láurenz’s team returned the ball on November 16.

Yo Soy De San Telmo

PEDRO LAURENZ - ALBERTO PODESTA - YO SOY DE SAN TELMO - MILONGA - 1943

The second ball was by Láurenz/Podestá in the form of Maldonado, another milonga by Alberto Mastra. There were just eight days between the serve and the attempted return.

Maldonado - Pedro Laurenz - Alberto Podestá 1943.12.09

Carlos Di Sarli - 1943 - Rufino - Maldonado

I think Di Sarli and Rufino missed the ball. Of course, it is a matter of taste what you expect from a milonga, but as a dancer (who adores dancing milonga) I would be quite confused with Di Sarli’s interpretations, and as a DJ, I wouldn’t play them at all. Di Sarli’s lingering elegance is great for tango but not for milonga. All the rhythmic joy Láurenz and Grané pack in their interpretations is absent from Di Sarli’s versions.

But that was not the whole match! Already on November 4 Di Sarli and Rufino recorded Todo, a tango by Hugo Gutiérrez and Homero Expósito, and Láurenz/Podestá returned the ball on December 9, the same day they recorded Maldonado.

Carlos Di Sarli - 1943 - Rufino - Todo

Todo - Pedro Laurenz - Alberto Podestá 1943.12.09

Now Di Sarli is on his own ground, and this clash of titans ends a dead heat. It is your choice to decide if you prefer elegance over rhythm and color or sustained melodic lines over the richness of detail.

In March 1944 a window of opportunity opened for Podestá when Rufino, his pain in the neck, finally left Di Sarli for good. Podestá quit with Láurenz, and in mid-April he was already recording with Di Sarli.

After Podestá

The loss of Podestá was not a catastrophe for Láurenz. During the past year he had established his position as a top-class musician, and business continued as usual. Carlos Bermúdez was hired as the new singer at the end of April.

April and May 1944 also saw the final round of the Láurenz vs. Di Sarli tennis match, but this time the players of this doubles game were mixed. The ball, tango Llueve otra vez by Juan José Guichandut, was served by Láurenz and Bermúdez on April 26, and Di Sarli returned the ball on May 25 – with Podestá! It is quite possible that Láurenz’s orchestra rehearsed the tango with Podestá before his departure, and the one-month interval between the recordings might indicate that Di Sarli arranged and rehearsed the tango for Podestá during this time. These interpretations convey different moods, but they are both masterpieces in their own right.

Llueve Otra Vez - Orq. Pedro Laurenz, canta Carlos Bermudez.

Today's Tango Is... Llueve Otra Vez - Carlos Di Sarli 24-05-1944

Láurenz’s version is in fact Grané’s masterpiece. The lyrics draw a parallel between a rainy day and the end of love, and Grané’s arrangement sketches this resigned and gloomy mood with shades of gray. The instrumental half introduces the atmosphere and the melodic material, but just before the singer starts, the lyrics come to life in music.

At 1:23 we hear raindrops (violin pizzicatos), and then some more raindrops at “Escucha, corazón, está lloviendo” / “Listen, heart, it is raining”. A lightning strikes at 2:15 - “y un látigo de luz me azota, relámpago de fiebre loca” / “and a whip of light beats me, a lightning of mad fever”. Right after that heavy rain beats the window – “La lluvia, sin cesar, golpeando en el cristal, renueva la emoción perdida.” / “The rain, unceasingly, beating the glass, revives the lost emotion.” Then at 2:31 the singer sees a ghost in the mist – “Y entre la bruma creo ver su imagen, igual que entonces, diciendo adiós.” / “And amidst the mist I think I see her image, just like when she said goodbye”.

Di Sarli’s versión, on the other hand, is neither resigned nor gloomy. One could say it’s defiant and full of fiery emotion. Rather than seeking shelter in the rain, the singer stands up against a storm, and Di Sarli’s left hand hits like thunder. There are pizzicato raindrops, of course, but the text is not illustrated in detail. It is a great richness of life that we might have quite the opposite views of one song like these two!

Things went on so well with Láurenz that he decided to hire a second singer – as most top-class orchestras did. His choice was Jorge Linares.

In August 1944 Láurenz recorded a tango composed by Héctor Grané, the only one he did record. The lyrics were by Justo Ricardo Thompson, and the title was Esta noche al pasar.

Pedro Laurenz - 1944 - Esta noche al pasar (Linares)

Both the song and the arrangement are very romantic. Láurenz seldom played left-hand solos, but here the solo at 0:38 compares to the grand solos played by Aníbal Troilo. It is also possible that the solo was played by Ángel Domínguez, Armando Brunini, or Benito Calvá, but normally solos were reserved to the orchestra leader if he was a bandoneonist. Anyhow, when Linares repeats the melody at 1:49 and 2:36, it is very touching. Tanturi, again, picked this tango into his repertoire in January 1945.

Everything seemed to be all right, and Láurenz was recording with Bermúdez and Linares every second month, but by the end of 1944 Grané dropped a bomb: he wanted to quit, which he did.

Láurenz without Grané

Láurenz seems to have been totally lost without Grané. He found Carlos Parodi to replace Grané at the piano but not as an arranger. He kept appearing on radio, but he didn’t record anything for one and a half years, which is understandable because, in the lack of an arranger, he had no new material to offer to the record company.

When Láurenz returned to the studio in September 1946, one of the two tangos he recorded that year was La Beba by Osvaldo Pugliese. Pugliese named this tango to celebrate the birth of his daughter Lucela Delma, known as Beba, on November 10, 1936. Láurenz’s version sounds very Pugliese-like, and it is possible that Pugliese, as a token of old friendship, wrote this arrangement for Láurenz in 1946, or then the arrangement is from 1936 when Pugliese played with Láurenz. The other tango recorded in 1946, Piedad, was probably arranged by Cayetano Cámara.

In 1947 Láurenz only recorded two De Caro tangos, Mala junta and Amurado, his old hit. This was in January, and after that, it seems that Odeón lost all interest in his orchestra.

For five and a half years Láurenz didn’t record anything, not a single track. In mid-1952 he made a contract with Pathé, a smaller recording company.

Grané without Láurenz

But what did Grané do in 1945? The answer is typical: He had his own orchestra. Little is known about the success of his band, but during the first months of 1945 he recorded two tangos of his own composition, Esta noche al pasar and Pueblo tango. The singer was.. <drum roll> Alberto Podestá! He had been working with Di Sarli for seven months and was now seeking new opportunities.

The shellac is a rarity of highest grade, but DJ Damián Boggio has managed to upload Pueblo tango to YouTube.

Alberto Podestá & Hector Grané - Pueblo tango

The orchestra sounds very much like Láurenz – well, like Grané. The main difference to Láurenz is that the bandoneon section is less prominent. Strong piano arrastres and the absence of bandoneon marcato, typical features of Grané, are both there.

If somebody could find the other side of the shellac, Esta noche al pasar, I would be very grateful to hear it. The interesting question is if Grané was using the same arrangement he had written for Láurenz or if we would hear a new one.

Podestá didn’t stay with Grané more than “al pasar”. In June 1945 he was already recording with Edgardo Donato, and later that year he joined the new orchestra of Francini and Pontier.

No documents can be found about the success of Grané’s orchestra, so apparently there was none. A musician has to make a living, and so Grané had to knock on a door he already knew.

Grané is Back!

By the end of 1947 Grané was back with Láurenz and stayed with him for the next six years or so. From our point of view, five years of silence now follow because the orchestra didn’t record anything from 1948 to 1951. Written history, however, tells that they were appearing at Marabú and La Enramada and on LR3 Radio Belgrano.

When Láurenz started recording with Pathé, the first numbers were Quejas de bandoneon, a popular classic, and Cuando me entrés a fallar by José María Aguilar and Celedonio Flores. Unfortunately the sound quality of available Pathé transfers is not very good. The singer is Alfredo Del Río.

Cuando me entrés a fallar - Laurenz

We can hear that things are not how they used to be. The arrangement is nice, but it is hard to say if it is by Grané at all. We can hear a sharp bandoneon marcato, which Grané has avoided so far. Strong piano arrastres are missing, and instead, the left hand plays legato bass, a feature that many pianists adopted from Orlando Goñi. Violin pizzicatos are also unknown in this arrangement. Perhaps the arranger is Grané after all because who else could it be? Maybe he just had to adapt to requirements set from outside.

The other two recordings Láurenz made in 1952 were La gayola, an old tango by Rafael Tuegols, and Amurado, Láurenz’s own “evergreen”.

Láurenz disbanded his orchestra in October 1953, but at that time Grané was already far away.

Monsieur Grané, Chef d'orchestre

In 1954 Astor Piazzolla came to Paris with his wife to study composition with Nadia Boulanger. Their budget didn’t allow staying at a hotel, but luckily they could enjoy the hospitality of a fellow countryman named Héctor Grané. Piazzolla thanked his landlord by recording Grané’s tango Haydeé with his Octeto Buenos Aires three years later.

Octeto Buenos Aires - Haydee

So Grané was already living in Paris and had an apartment to accommodate guests, but we know nothing about how he ended up there and what contacts he had in the city. Anyway, in 1955 he also had an orchestra and started recording Argentine tango and pieces of other Latin genres. Adiós muchachos, an iconic song by Julio César Sanders and César Vedani, was among the first ones.

Adios Muchachos

This doesn’t sound exactly like Argentine tango in our ears, does it? The piano is OK, the bandoneons are OK, but the violins! When they play legato, they sound more like Mantovani than a tango orchestra, and even their accented staccato is soft and “nice”.

We must bear in mind that even in Buenos Aires tango was in decline, and we cannot expect that people would buy danceable Golden Age tango when they just wanted something for “easy listening” at home. The violinists in Grané’s orchestra were probably studio musicians who played all kinds of popular music, and the kind of popular music where a violin section was needed was certainly not any kind of rock’n’roll. On the other hand, the record company must have had a view of what kind of music was selling, and they might have told Grané that “this is the way you should play, nice and easy!”

In Argentina things were not much better, and for comparison we can listen to Osvaldo Fresedo’s interpretation of Adiós muchachos. WARNING! This performance contains added sugar, and if you feel sick, you don’t have to listen the whole sample.

Adiós muchachos (Remastered)

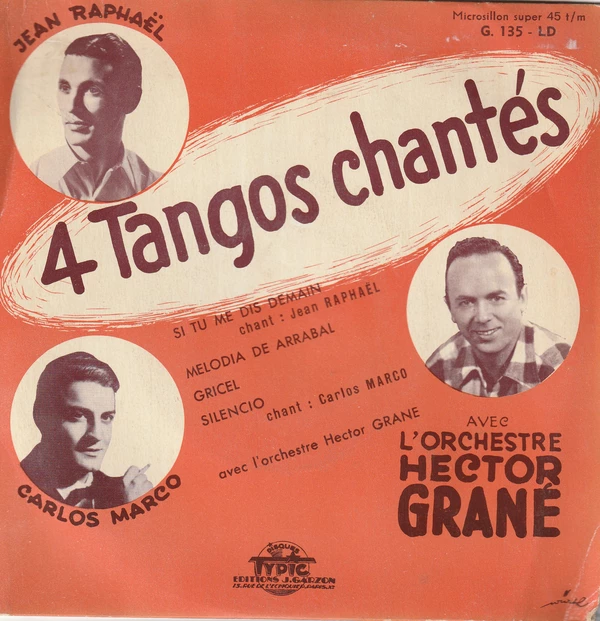

To me, songs are the best part of Grané’s work in Paris. If you don’t expect a danceable tango, you can freely enjoy the music and Grané’s genial arrangements. Grané had two singers with his orchestra.

The first singer was called Jean Raphaël, and he was very “French”. He had a high and light tenor voice like Tino Rossi but still higher. He sang in French. Poema by Eduardo Bianco and Mario Melfi was well known by the French audience because it was composed and premiered in Europe.

Poema

The other one was called Carlos Marcó, and his Rioplatense Spanish reveals that he was from Argentina or Uruguay. It is a great shame that recordings by this marvelous singer cannot be found anywhere else, only those made with Grané.

Marcó’s interpretation of El último organito by Acho and Homero Manzi equals that of Rivero and Troilo.

El Ultimo Organito

Grané’s farewell to his home country was recorded in 1957. The song Adiós mi Argentina was composed in 1954 by Julio Falcón who was born in Spain and died in France but grew up in Argentina. Probably he also wrote the wistful lyrics to this song.

Adios Mi Argentina

I would like to end our journey after Héctor Grané with his own composition to his own lyrics, the song Aquel Poeta. Granés footsteps vanish in the unknown, but his art lives on.

Aquel Poeta (feat. Carlos Marco)

Dejó sus padres y con un poeta,

Se vino al centro un carnaval de antaño

Amó al poeta, al carnaval

Después, un gran bacán de lujo vestía esa pebeta

Igual que todas las demás mujeres

que son hermosas desechó deberes.

A los placeres se entregó en loca diversión

Y ahora vencida implora amor.

Este tango es para vos,

Te lo dedica aquel poeta.

En mi pobre corazón

Viviste siempre, piba coqueta

No te voy a reprochar,

pero una cosa quiero decirte

Con mi amor no ibas a estar

Así tan sola y triste en este bar.

Ya no es tu cara de color rosado,

Tus manos blancas como flor se ajaron

Y tus cabellos como el sol, cenizas solo son

Llorando las ruinas del pasado

Como una espina tu mirar me hiere

Por eso solo te diré muy breve

Reconocerte fue sentir deseo de llorar

Perdona, deseos de morir

Discuss this this topic at Facebook