The Treasure in Troilo's Cupboard

Aníbal Troilo, El Bandoneón Mayor de Buenos Aires (1914 – 1975), is one of the cornerstones of tango music, and the pile of manuscripts found posthumously in his cupboard is a priceless treasure. The material, consisting of 489 arrangements for Troilo’s orchestra, was scanned to pdf by Javier Cohen and Juan Carlos Cuacci at EMPA, Escuela de Musica Popular Avellaneda, from 2011 to 2014. In 2019, the originals were donated to Instituto de Investigación en Etnomusicología of Buenos Aires. Currently, there’s a project going on at the institute named Arreglos inéditos de Piazzolla para Troilo aimed at publishing the unpublished arrangements by Astor Piazzolla. The first edition just came out containing tangos Nostalgia and Lo que vendrá as well as Azabache, a milonga candombe.

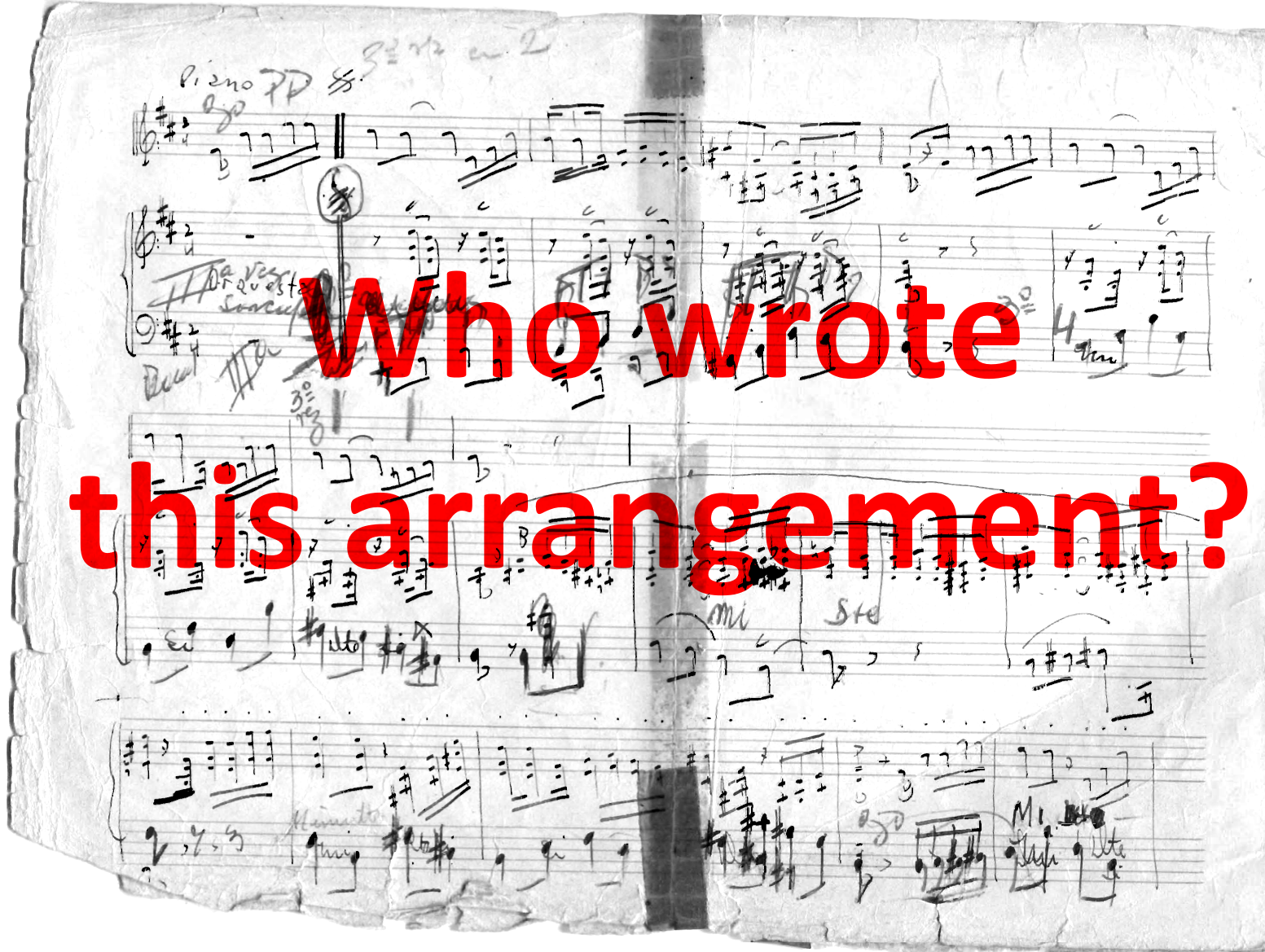

Azabache was Piazolla’s debut as an arranger. These are the first pages of his manuscript and the published edition; there is no orchestral score in the former and no parts in the latter, but one can identify the first five measures of the piano part in both versions.

One of the reasons why the institute chose Piazzolla as their starting point must be that his musical handwriting is quite readable – he had been studying composition with Alberto Ginastera since 1939 – and no parts are missing. The same cannot be said about a lot of the manuscripts in the collection, and the earlier arrangement you take, the more haphazard and incomplete it is. One of these “less readable” ones is Malena.

Malena Canta el Tango

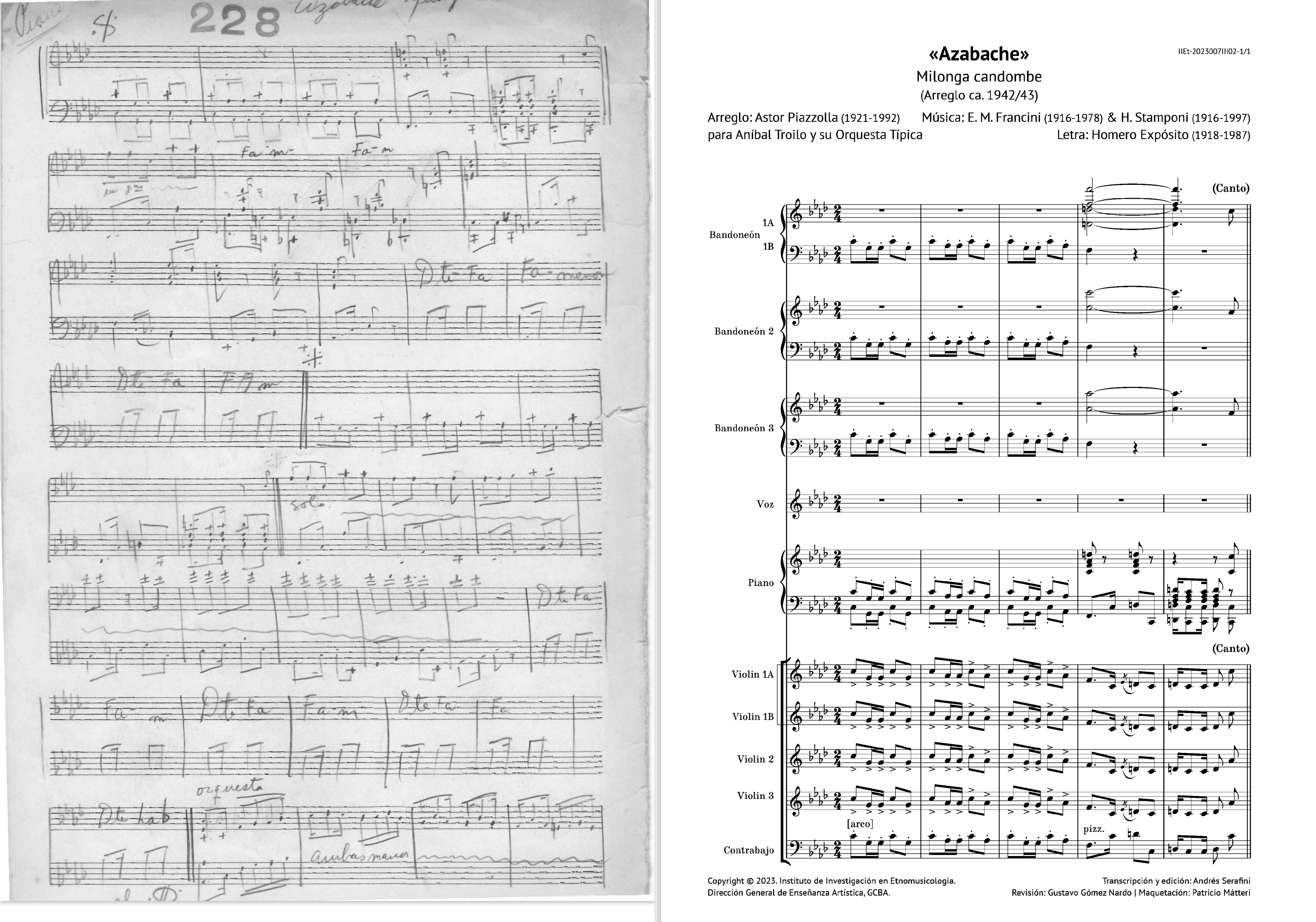

I have a copy of the digitized manuscripts and often use them to aid in transcribing recordings by Troilo’s orchestra or, I must confess, to rip off ideas for my own arrangements. When I was working with Malena (1942) and opened the pdf, the sight was a bit shocking:

These first two pages are supposed to be the piano part of the arrangement, but at first glance, they are just a terrible mess. If you look closer, however, you will see that all noteheads are quite clearly either on staff lines or spaces, and the rhythms are unambiguous, so in principle, the texture is unequivocal. Nevertheless, the overall impression of the pages is far from user-friendly.

The numerous strikeouts and alterations on these pages reflect the well-known fact that Troilo, who could not write music himself, often wanted changes in the arrangement when he heard the outcome at a rehearsal. Some alterations might have been done in 1952 when Troilo re-recorded Malena with Raúl Berón.

From bar 9 on, the piano does not play as written: not the chords with the melody on top, but something else. In fact, this is not the part that the piano is supposed to play but a compressed general score that contains all the notes the other instruments are to play. We might think that this is what the arranger writes first and then extracts the bandoneon and violin parts to their respective pages.

The first three staves belong to one system, and at the beginning, the piano plays the melody that is on the first staff. The syncopated accompaniment on the second staff is played by bandoneons and violins, and the third staff by the double bass. After the solo ends in bar 9, the piano plays with violins and bandoneons for a while but adds some embellishments of its own that are not notated. At the bottom of the first page, piano goes its own way and plays this rhythmic pattern:

The boogie-woogie-like pattern is known as marcación bordoneada (or bordoneo), the specialty of Orlando Goñi, Troilo’s pianist when Malena was recorded for the first time.

This might be the right spot to listen to Malena played by Troilo, Goñi, and others and sung by Fiorentino:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnN4mUO5IW8.

At times, the piano plays together with violins and bandoneons, but most of the time it plays chord accompaniment in the rhythm of the bass part, especially when the singer sings. This is called marcato en cuatro. The piano also plays some bridge passages that are not written. To summarize, this “part” is mainly a memory aid or an extended lead sheet for a pianist who plays some things that are written and other things that are not written. The arranger must have had strong trust in the pianist when leaving so many things open or…

Was it Héctor Artola?

Tango Masters: Aníbal Troilo by Michael Lavocah has a discography containing the name of the presumed arranger for almost all of the recordings made by Troilo. Lavocah probably bases this information on Aníbal Troilo, perfil y discografía by Arturo Dorned Linne, which I, unfortunately, haven’t got access to. Anyway, the arrangements recorded in 1942 are all but one attributed to Héctor Artola (“HA”), and so is Malena.

Héctor Maria Artola (1903 – 1982) began his career as a pianist, bandoneonist, and orchestra leader, but from 1940 on, he growingly devoted himself to arranging and orchestrating tango music. In 1942, he seems to have been very busy with Troilo, but there is one major problem: Almost all the recordings marked with “HA” in the discography have no written counterpart in the EMPA collection of scanned scores – as if Artola would have paid a visit to Troilo’s house after his death and taken off his own arrangements from Troilo’s cupboard. The alternative explanation could be that there have never been such arrangements by Héctor Artola.

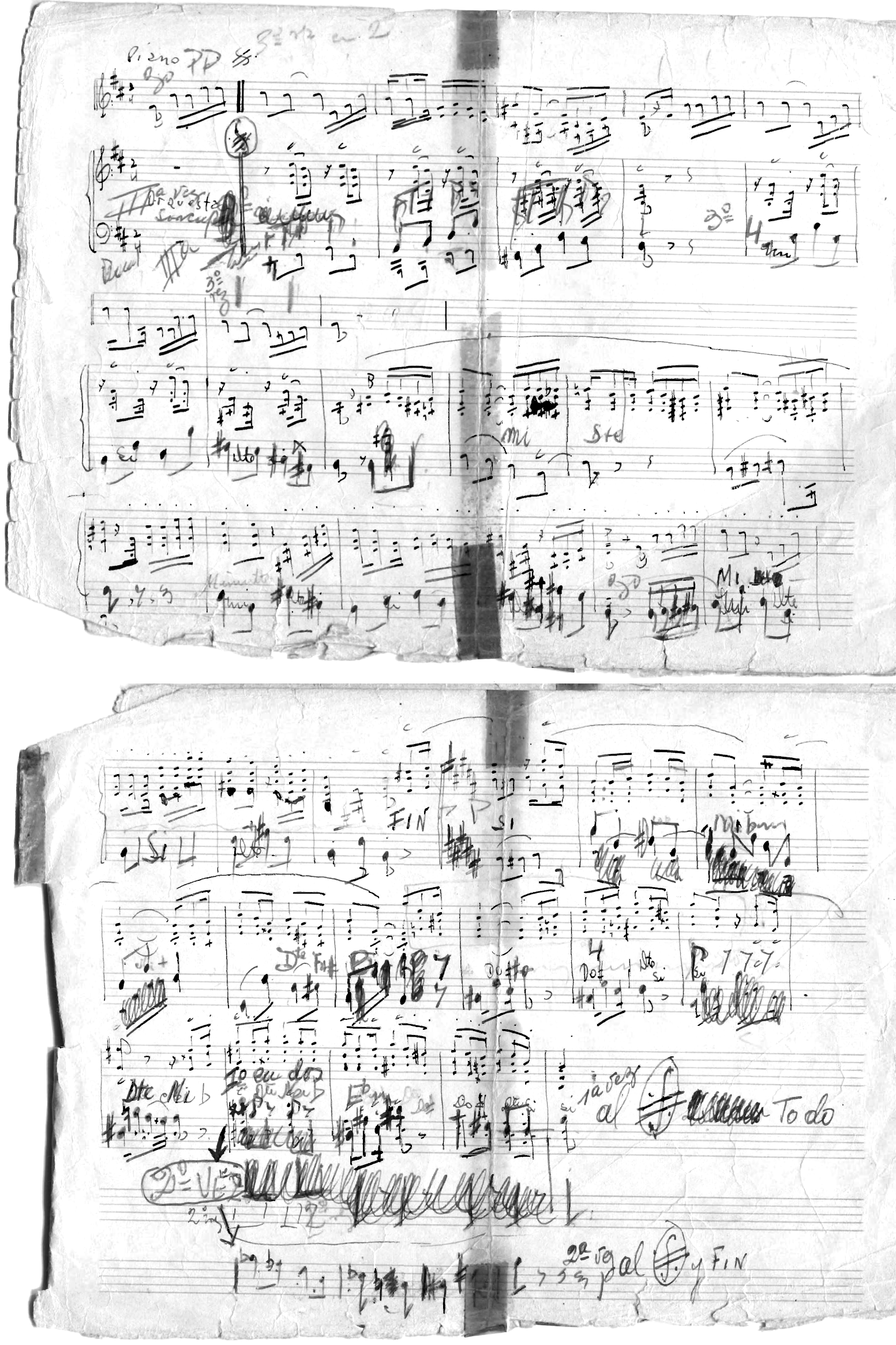

The arrangements attributed to Artola and found in the cupboard form a very heterogeneous collection representing different handwritings, but from April 1943, we can see two arrangements that were likely to be written by a professional arranger in consistent handwriting. They are Tango y copas and Soy del 90.

The piano part of Tango y copas has a totally different look from that of Malena. The handwriting is good, and to guide the performer, the part even contains such details as dynamic markings, but what is most important is that this is a part that the pianist is supposed to play as it is. For instance, bars 9 to 14 neither contain the violin melody nor the bandoneon rhythm, just the marcato and bordoneo accompaniment the piano plays from 0:16 to 0:28 in the recording. The person who wrote this might be Héctor Artola or Argentino Galván, but that would be the subject of another investigation.

The Clef is the Key

Since the Renaissance, artists have signed their paintings and prints, but in 1942, tango arrangers didn’t do that. The first signature I have found in these manuscripts is by Argentino Galván from 1945. Nevertheless, arrangers subconsciously "sign” their work whenever they write something on a music staff.

When arrangers and composers write music on paper, their handwriting may vary depending on the situation they are in. When in a hurry, some of them often draw downward-pointing stems on the wrong side of the note heads, whereas another time they might obey the rules of musical notation more carefully, for instance. However, there is an element of musical notation that is quite invariable within the output of one writer yet takes various forms from one writer to another. This element is the clef, especially the treble clef.

When a professional musician starts writing a new music staff, they draw the clef automatically and instinctively, not thinking of the clef itself but the notes to follow. This makes the clef kind of a musical fingerprint that might be drawn more or less hastily, but it always has the same features that come from the subconscious.

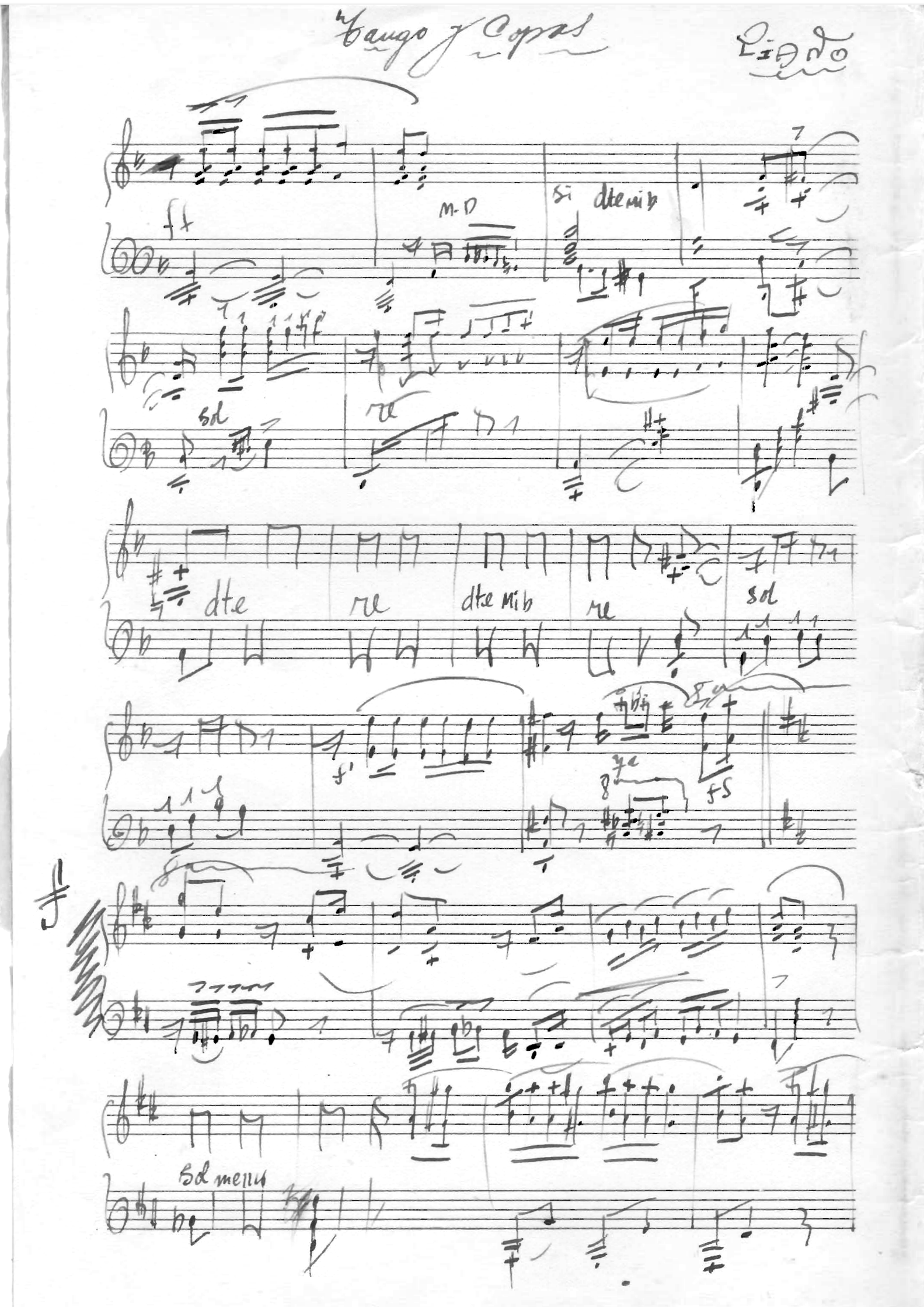

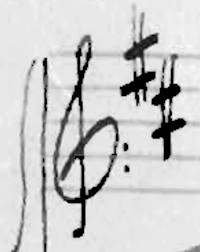

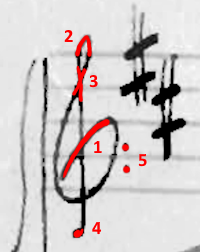

Let’s look at the clefs found in the three samples above!

|

Azabache (Piazzolla)

|

|

|

Tango y copas

|

|

|

Malena

|

|

Now, let’s look at the distinctive features of the third one!

- The curl marking the second line (the place of G4) is not round and starts with an upward-slanting line that is almost straight.

- The loop at the top hardly rises above the fifth line.

- The crossing that closes the loop is above the fourth line.

- The hook at the end is more like a ball than a hook.

- And then an exceptional feature: The writer marks the second line with two dots the way the third line is normally marked after the bass clef. These extra dots do not comply with current Western music notation rules.

So where do we find this very distinctive clef? The answer is: In all the arrangements from the oldest one found in Troilo’s cupboard (Toda mi vida) to Gricel that was recorded on October 30, 1942.

|

Toda mi vida

|

|

|

Gricel

|

|

Between these two milestones, 11 arrangements bear the same “fingerprint”: El bulín de la calle Ayacucho, El cuarteador, Tu diagnóstico, Tinta roja, Sencillo y compadre, Malena, Papá Baltasar, Pa’ que bailen los muchachos, Un placer, Suerte loca, El encopao, and Tristezas de la calle Corrientes.

Who Was this Guy with the Terrible Handwriting?

I cannot think of anybody other than Orlando Goñi as the author of these manuscripts. There are no arrangements bearing the distinctive clef after Goñi left the orchestra in August 1943 – except La cumparsita, recorded in November 1943, but it was such a staple in any orchestra’s repertoire that it must have been arranged for use on gigs much earlier.

When Troilo formed his orchestra in 1937, he did it in close cooperation with Goñi. They got acquainted when they both played in orchestras led by Manuel Buzón and Juan Carlos Cobián, and they shared a view of the future of tango. It has also been said that it was Goni who urged Troilo to put up an orchestra of his own.

This spirit of shared views and cooperation must have had a significant impact on the early arrangements of Troilo’s orchestra. It is worth noting that most of the arrangements I attribute to Goñi, if not all, don’t contain a part for the first bandoneon. Troilo didn’t need one because what he was supposed to play was already in his head. This suggests that the arrangements were as much teamwork as Goñi’s creation, and I think this cooperation between Troilo and Goñi was essential in building what we know as the style of Anïbal Troilo’s orchestra.

But why do these “fingerprinted” arrangements cease after Gricel? It must be due to Goñi’s growing addiction to drugs and alcohol. It is a known fact that he was repeatedly absent from gigs, in which case Astor Piazzolla had to stand in for him at the piano, and it is likely that similar things also happened at rehearsals. Goñi could or would not maintain his active role in creating arrangements, which gave way to other arrangers such as Astor Piazzolla. Eventually, things got so bad that Troilo had to sack Goñi in August 1943.

What to Do Next?

Troilo’s cupboard was a treasure chest, and there are lots of things in this material that can change our view of the art of Aníbal Troilo. For one thing, the list of arrangers must be rewritten, which involves comparative analysis not only between the manuscripts in this collection but also with manuscripts for other orchestras by verified arrangers.

Read more about Orlando Goñi and his special piano style in my recent blog article.